Stop 11: The Meyerhoff Family

Düsseldorfer Str. 17 – go to map – go to starting point

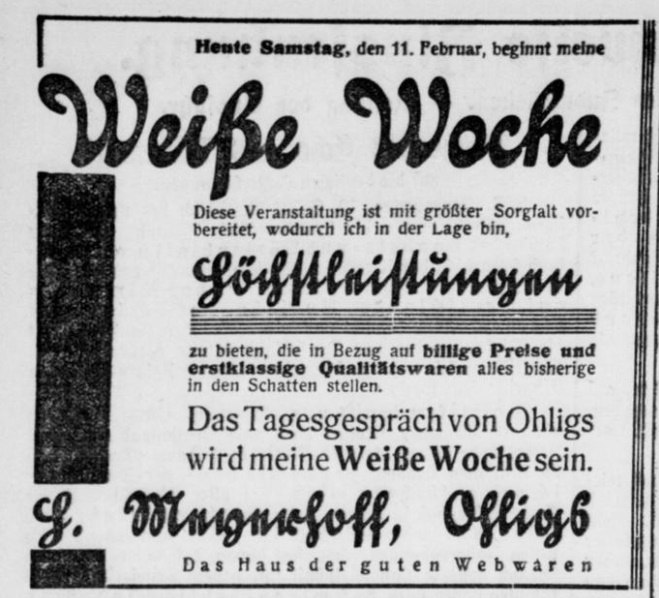

After the manufacture and fashion store “S. Meyerhoff, Manufaktur- und Modenhaus“, located at Düsseldorfer Straße 49, went bankrupt, Henriette Meyerhoff had opened a new business in 1932, registered under her name at Düsseldorfer Straße 17. Two auxiliaries worked at the new store that was advertised for in the “Ohligser Anzeiger” as [in translation] “S. Meyerhoff, house of fine woven goods”.

After the National Socialists had seized power, the economic existence of the Meyerhoff family in Ohligs was threatened, as was that of their relatives in Körbecke and Duisburg. They all felt the effects of the boycott of Jewish businesses as well as of the advancing exclusion and disenfranchisement of Jewish citizens.

Henriette’s daughter Grete, together with her husband Heinrich Rosenblatt and their daughter Hella, managed to emigrate to the USA on 29 October 1938. The family departed from Rotterdam and arrived in New York only a couple of days before the Jews remaining in Germany had to endure the nationwide pogroms. In the night of 9–10 November 1938, a police officer in Ohligs forced Simon Meyerhoff to clear the Düsseldorfer Straße of the shattered glass that National Socialists had left there when raiding his store.

Henriette’s son Fritz Marx, registered in Duisburg at the time, was among the Jewish men that had been deported to Dachau in November 1938. After his release, he managed to flee to Belgium and, in May 1939, eventually emigrated to the USA.

Simon Meyerhoff’s brother Max and his wife had moved from Körbecke to Düsseldorf where they lived at Steinstraße 60, presumably since January 1939. The Lubascher family, having moved in from Solingen, ran a restaurant and guesthouse there until the night of the pogrom. In the course of the year 1939, the house was turned into a so-called “Judenhaus” (literally “Jew house”). Cilly Rosenbaum, a neighbour of the Meyerhoff family in Ohligs, also moved to this address in May 1939.

Solingen’s housing office also forcefully relocated Jewish families and merged them in houses of Jewish owners. For that reason, Simon and Henriette Meyerhoff had to move into the house of Toni and Berthold Westheimer, located at Malteserstraße 23, on 3 August 1939.

When, in 1941, the Nazis started deporting Jews to the eastern ghettos and extermination camps, Simon and Henriette Meyerhoff were among the first victims. Together with fifteen other Jews of Solingen, they were deported to the Ghetto of Litzmannstadt (Lodz) on 26 October 1941. On 17 December 1941, Simon Meyerhoff’s brother Max wrote to Solingen’s religious community [in translation]:

“I hereby kindly ask if you could provide me with any information on where the transport headed east as of 27 Oct. was going. This is about spouses Simon Meyerhoff, Malteserstrasse 23. Maybe you have already come to know their current address. I’d be grateful for a swift reply in this matter.”

City Archive of Solingen, Ve 44-5 (translation M.B., 2021)

We don’t have any proof of a reply. On 8 May 1942, Simon and Henriette Meyerhoff were killed in a gas van at Chelmno extermination camp.

The “Weiße-Rose-AG“ (extracurricular club named after the German

resistance group) of Solingen’s comprehensive school Geschwister-Scholl-Schule regularly takes care of the Stolpersteine at Düsseldorfer Straße. Photo: Daniela Tobias

At the time, Henriette Meyerhoff’s children in the USA did not yet know about their parents’ fate. Fritz Marx, now going by the name of “Fred”, signed up for the US army on 14 August 1942. He was transferred to Algiers where the pianist arranged the music for the troop musical “Swing, Sister Wac, Swing” in 1943. However, the show was cancelled again after only four performances in January 1944.

On 18 February 1944, journalist Tania Leshinsky interviewed Fred’s wife Alice Marx for the New Yorker periodical “Aufbau“. Excerpts of the article read [in translation]:

“‘Fred has always been a musician’, his wife Alice tells me – he was the student of Teichmüller, he was a pianist and, after that, conductor. You can imagine that he was never interested in jazz. When he came to America five years ago, he immediately found a job as pianist in a nightclub, and that was – in Yorkville. And then came in the new, the American! He started playing jazz, music the American way (…). He is also very successful with his own compositions. Almost all of his seven popular songs turned out to be a hit. (…) ‘And what are your and his plans for the future?’ I asked. ‘Music and music, over and over again. The cheerful, American music that makes one forget everything – even Dachau.’”

“Begegnung in Algier“, article in the periodical “Aufbau“ of 18 February 1944 (translation: M.B., 2021).

The alleged escape from Dachau in this article is very unlikely since there are documents about his regular release and there is no evidence that any escapes happened during this time. Source: “Aufbau“ Archives at JM Jüdische Medien AG, Zurich via archive.org.

After the war was over, Fred Marx still worked as musician in New York, but didn’t make a career in show business anymore. He died in New York on 11 July 1977. His sister Grete and her family had settled down in Los Angeles and had changed their last name from Rosenblatt to Roy. Greta Roy died in 1989, ten years after her husband Heinrich.