By Armin Schulte and Daniela Tobias, translated from German by Miriam Braun, Autumn 2021

- Stop 1: The Coopman Family

- Stop 2: The Strauss Family

- Stop 3: Henriette Marx

- Stop 4: The Rosenbaum Family

- Stop 5: The Davids Family

- Stop 6: The Bassat Family

- Stop 7: The Steeg Family

- Stop 8: The Zürndorfer Family

- Stop 9: The Steinberger Family

- Stop 10: The Wallach Family

- Stop 11: The Meyerhoff Family

- Stop 12: Ohligs Station

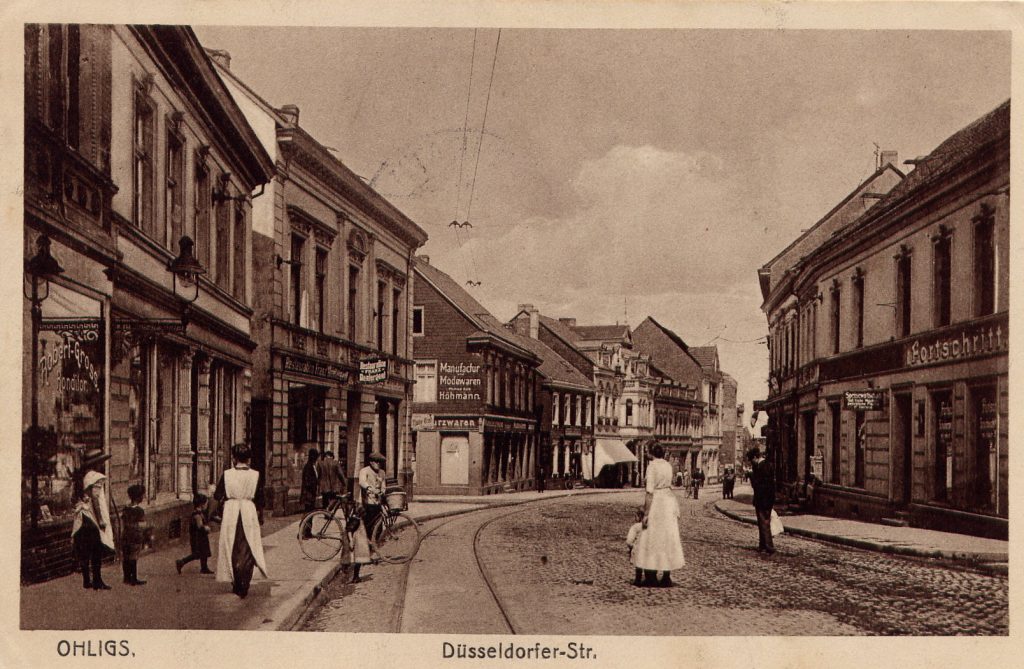

The tour starts at the marketplace of Ohligs and ends at the main station. The route is barrier-free and covers a distance of about 400 meters.

Stop 1: The Coopman Family

Düsseldorfer Str. 76 – go to map – go to starting point

Our tour starts at the marketplace of Ohligs. Here we are at Düsseldorfer Straße 76 where merchant David Coopman once had a men’s and boy’s clothing store. Like most Jewish merchants that settled in the emergent centre of Solingen-Ohligs around the turn of the century, Coopman originally came from a rural area. His parents’ generation was mostly working in the cattle trade, one of the few jobs allowed for Jews in their days, with some of them at least making enough money for some savings. So, once the Jews were granted legal equality, said parents could finance good education and training for their children and, as a consequence, their offspring rapidly advanced socially.

David Coopman was born on 30 December 1877 in Linnich, close to Jülich, and was the son of horse trader Heumann Coopman and his wife Bertha. David’s mother already had two daughters from her first marriage, Regina and Emma. After David, the couple also had two girls together, Jenny and Julie, and another son, Jakob.

In 1885 and 1899, sisters Emma and Jenny Coopman already stayed in Solingen for a while. Julie Coopman also lived there for several months in 1903.

On 25 November 1897, David Coopman moved from Hilden, where his sister Emma and her husband Josef Krämer had opened their own business that year, to Ohligs. At first, he was registered as salesclerk at Julius Wolff’s on Düsseldorfer Straße 43. Wolff was probably related to him through his wife Bertha Coopman.

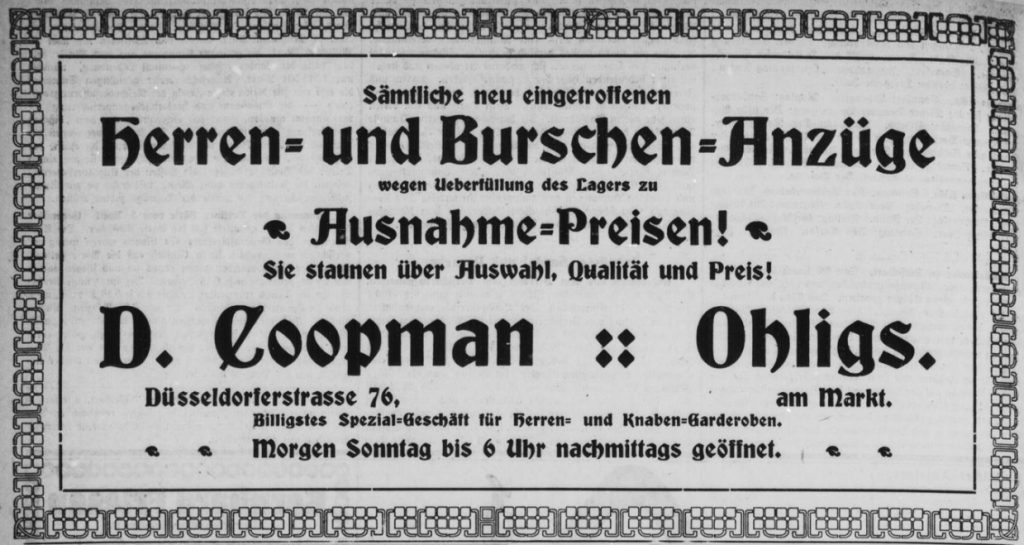

David Coopman did his military service from 1898 until October 1901 and returned to Ohligs afterwards. He was registered as self-employed merchant since 1908 and was in charge of his own store for men’s clothing. He regularly placed advertisements and promoted his business via newspaper supplements. In his different ads, he praised his clothing store as [in translation] the “cheapest store for men’s, boy’s and worker’s robes”. His sister Julie moved to Ohligs in 1916 and started working for him as sales assistant. She remained unmarried, as did David. The Coopman store was presumably flourishing, it never belonged to Ohligs’ larger textile stores though.

Since the National Socialists had seized power in 1933, the textile store’s daily business became subject to more and more restrictions as a result of the Nazi’s antisemitic persecution policies. David Coopman died on 12 October 1937 at the municipal hospital, after undergoing surgery for inguinal hernia. He was buried at the Jewish cemetery in Solingen. His tombstone, a work by sculptor Leopold Fleischhacker of Düsseldorf, is inscribed with [in translation]: “Only the forgotten are dead.”

After David’s death, his sister continued to run the store at first, but it eventually closed down. Julie Coopman moved to Cologne on 29 July 1938. From there, she was deported to the Ghetto of Litzmannstadt (Lodz) on 30 October 1941.

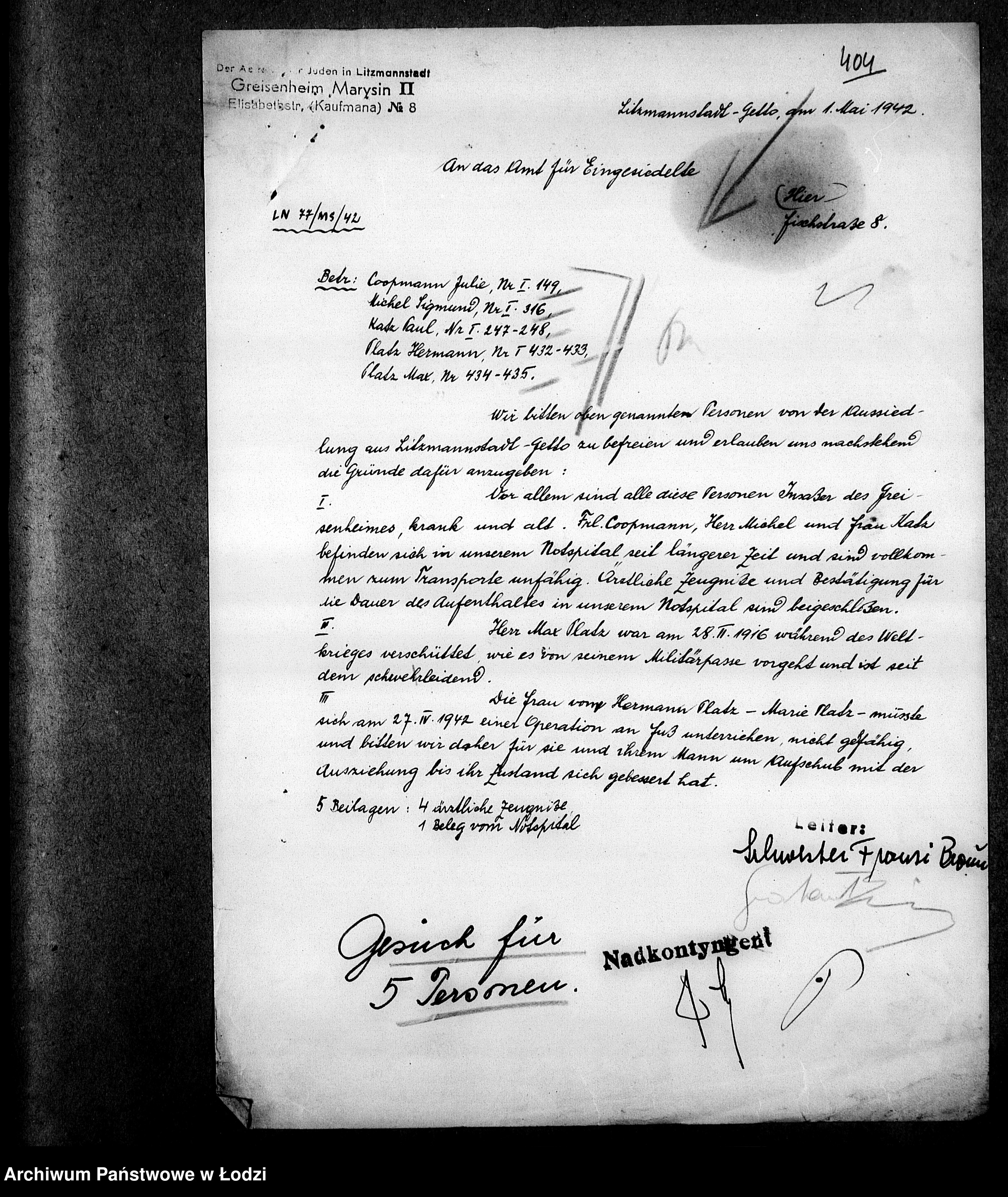

There is a harrowing letter, written by the directress of the “Greisenheim Marysin II“ (literally “Old People’s Home Marysin II“) and dated 1 May 1942, extant from the ghetto. Addressing the “Amt für Eingesiedelte” (literally “Office for In-Settlers”), she pleaded for the life of Julie Coopman and four other, sickly people [in translation]:

“We ask to exempt the persons mentioned above from the expulsion from the Ghetto of Litzmannstadt and would kindly like to put forth the following reasons for the request: first and foremost, all of these persons are inmates of the Greisenheim, they are sickly and old. Ms. Coopmann, Mr. Michel and Mrs. Katz have been in our makeshift hospital for quite some time now and are absolutely unfit for transport.”

Request for postponement of expulsion from Lodz ghetto, dated 1 May 1942 (translation M.B., 2021).

Request for postponement of expulsion from Lodz ghetto, dated 1 May 1942.

Source: State Archives Lodz APL PSZ, sig. 39/278/0/19/1290, sheet 404

Julie Coopman survived the letter by a few weeks only. She died on 6 June 1942, still in the ghetto.

Julie’s and David’s brother and sisters all fell victim to the Holocaust, as did their respective spouses and children. Only their nephew Bernhard Krämer and, probably, his sister Klara actually survived the war. The National Socialists had managed to almost erase the Coopman family completely.